CHARLOTTE, N.C. (CN) — Chris Peake remembers growing up in West Charlotte in the 1970s. As a boy, he worked at the Mr. Quick store on South Hoskins Road in the Thomasboro-Hoskins neighborhood.

Working in the shadow of a bustling egg-processing facility behind Mr. Quick, Peake cleaned the parking lot every day until it was spotless. He spent his earnings on arcade games and food at the store.

Growing up, Peake didn’t have to worry about access to fresh food. John’s Grocery Store was just up the road from Mr. Quick. There was another grocer up on Bradford Road. Trucks lined up at the egg factory, highlighting the link between Peake’s home neighborhood and the region’s farms and food sources.

It was a thriving community with everything it needed in one place. “This was like ‘Happy Days,'” Peake, now 53, recalled last week in an interview with Courthouse News. But the community has changed since then, Peake said as he stood in the Mr. Quick parking lot. And with those changes came a sharp decline in healthy food options for local residents.

It started in the ’80s, when larger supermarket chains arrived in the neighborhood, bringing new competition. Local grocers struggled to keep up and shut down. Then the larger supermarket chains left, too.

Fast forward to today, and the Thomasboro-Hoskins community has few if any options for fresh food and produce. Even the egg-processing plant is gone, its old lot left vacant for years.

The Hoskins neighborhood — like many parts of Charlotte’s West Side and other Black neighborhoods — is now considered a food desert, lacking immediate access to fresh and affordable food options. Only 1.2% of the neighborhood’s housing units are within a half-mile of a full-service chain grocery store. Compare that to the county-wide average of 30.4%.

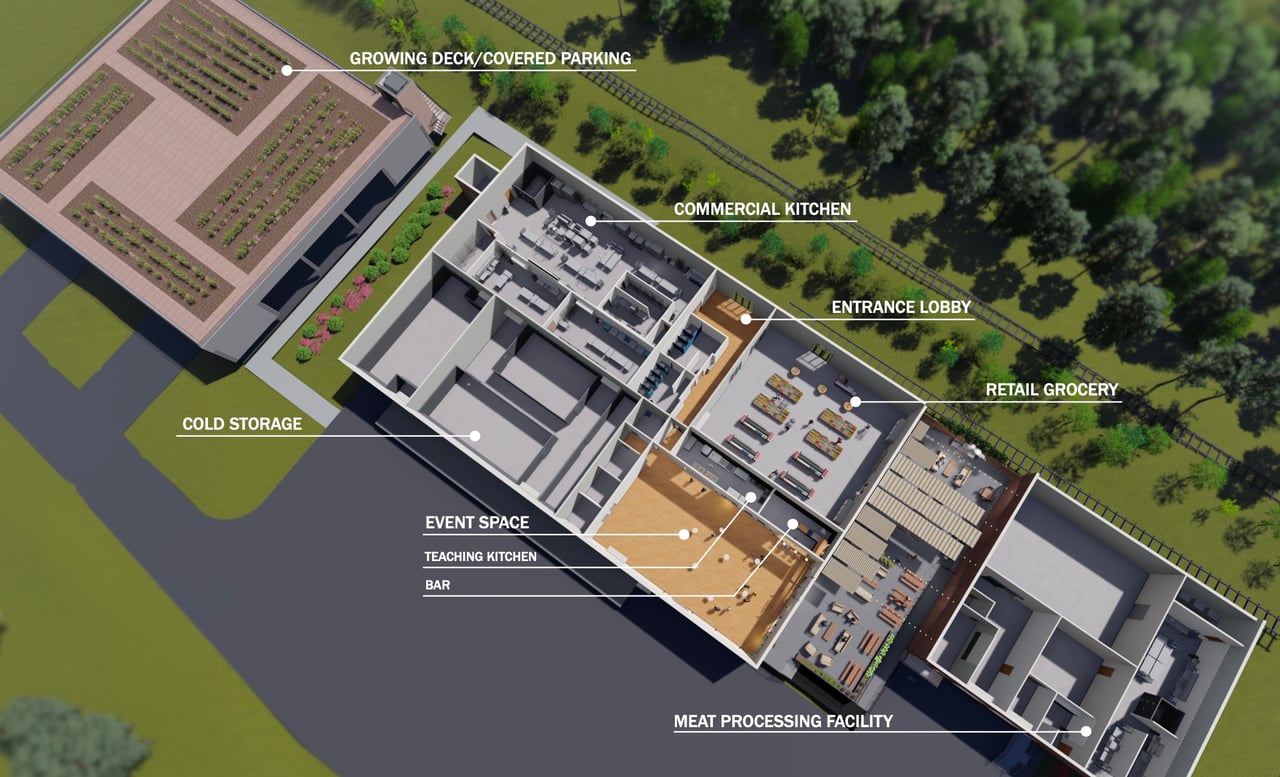

Now, at the site of the old egg-processing plant on South Hoskins Road, the nonprofit Carolina Farm Trust has begun construction of what it envisions as a potential part of the solution. The facility will one day become a 20,000-square-foot grocery store and distribution center — one that backers say could serve as a model for lifting up the whole food system, from small regional farmers to residents in food deserts.

The facilities will be locally staffed and feature produce from regional farms. It will have a commercial kitchen and a wholesale distribution center, where the Farm Trust will create and distribute its own products sourced from those partner farms.

The kitchen and distribution center will complement and help fund other services at the facility, including a butchery and meat processing center. That’s on top of public-facing amenities for the West Charlotte community, including a retail grocery store, a public teaching kitchen and community event space.

The goal is to do more than just build a grocery store, says Carolina Farm Trust CEO Zack Wyatt. Instead, he argues the project will help build up infrastructure for a bigger vision: a whole new local food system that lifts up local farms and gives all communities sustainable access to healthy foods.

“Part of what we’re trying to do is create a system where we’re actually meeting the need” for healthy, nutritious and accessible food, Wyatt said. Wyatt and other backers want to make the project self-sustaining, so that “we’re not waiting on a volunteer, we’re not waiting on a [corporation] to give a donation, we’re not waiting on the public to give a donation.”

For Peake, the local resident, the plan represents a sort of full-circle moment. He will helm the facility as its general manager, returning to the egg-processing facility that once loomed over him as he cleaned the parking lot at Mr. Quick as a boy.

Peake was working as a car salesman in nearby Statesville when Wyatt first approached him with the opportunity two years ago. Peake had found success in the car business. Still, his heart had always been in Charlotte’s West Side, where he spent most of his life, and in particular in the Thomasboro-Hoskins neighborhood, where he grew up.

He’d always had “a yearning to serve,” he said, especially after an aortic dissection in 2008 nearly killed him — and taught him the importance of healthy eating.

Talking to Wyatt, Peake learned for the first time about the challenges facing the country’s food systems — including a frequent lack of healthy food options in places like Thomasboro-Hoskins. “Once you know, you can’t unknow,” he said. He grew concerned about the lack of investment and food options in his home community and wanted to be part of the solution.

Fighting food insecurity in Charlotte

Across the United States — and even just in Charlotte — Thomasboro-Hoskins residents aren’t alone in their struggle to access healthy food. Around 15% of households in Mecklenburg County are considered food insecure, according to county data, meaning they have a reduced quality and variety of diet.

Access to nearby grocery stores is only part of the equation, said Colleen Hammelman, an associate professor at UNC Charlotte who studies social justice and urban food systems. Income and housing costs can also limit how much households are able to spend on healthy food.

Meanwhile, lack of reliable transportation options might also make food shopping difficult. By themselves, new grocery options alone are “rarely enough to help somebody overcome food insecurity,” Hammelman said in a phone interview last week.

Even still, residents of so-called food deserts like Thomasboro-Hoskins are particularly vulnerable to food insecurity, Hammelman said.

The lack of reliable food options in disenfranchised and minority communities is no accident, she added.

As big grocery-store chains weigh new locations, they try to identify areas that are most likely to generate a profit. As a result, such stores tend to coalesce around wealthier neighborhoods, while poorer neighbors are often determined to be not sufficiently profitable.

That’s on top of other challenges, Hammelman said — especially as minority communities are particularly susceptible to food insecurity. Research shows that food deserts often occur in communities of color with a history of “redlining,” or disinvestment due to racial discrimination.

Boosters like Hammelman say non-traditional or non-profit grocery stores like the Carolina Farm Trust project can help address some of these challenges by offering a model food system that isn’t just about profit.

With a focus on regional sustainability, local suppliers and local job growth, projects like this are a “great way [of] lifting up the entire food system,” Hammelman said. They’re one answer to the question “if the regular grocery store calculation isn’t making sense, what’s something else we can build here?”

The Carolina Farm Trust project is Hoskins isn’t the only new Charlotte grocery store trying to answer this question. In the West Boulevard corridor a few miles away from Thomasboro-Hoskins, The Three Sisters Market, a co-op grocer and farm, recently opened after receiving city funding.

Before it opened, zero nearby households lived within a half mile of a grocery store. Now, they have Three Sisters. It’s important that these efforts be community-led, Hammelman said, so that local residents get a say in what goes on the shelves.

A community gathering place

The new grocery project in Hoskins fits with the Carolina Farm Trust’s work to provide revenue and distribution streams to prop up local farms.

As residents of food deserts struggle to access healthy food, small farms in North Carolina are also facing their own challenges, including quickly shrinking acreage across the state.

Wyatt, the group’s CEO, said that the Trust had long envisioned a distribution center like this one. They wanted to place it in an area where it would have high impact — a food-insecure neighborhood like the area around South Hoskins Road.

In 2021, a contact told him the old-egg processing facility was available. It seemed like a perfect match. The team began bringing the center to life. Wyatt began to connect with local residents and eventually found Peake.

The new facility is expected to be built out in phases. The first part — the commercial kitchen — is slated to open in spring 2024.

Phase two will feature the retail concept, teaching kitchen, butchery component and event space. Fundraising efforts are underway for that project right now. That’s on top of already sizable public funding: more than $10 million combined from the City of Charlotte, Mecklenburg County and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

For their part, Charlotte-area officials hope the Trust’s project will help address issues of food accessibility in Hoskins.

At a groundbreaking event for the project in August, Mecklenburg County Manager Dena Diorio said officials had tried to pitch grocery businesses on the neighborhood but had been unsuccessful. From a profit perspective, some businesses felt it just didn’t make sense to invest here.

“The companies didn’t come, and they didn’t build,” Diorio said — but now the Trust’s project would bring fresh food and new employment opportunities to the community. The new facility, she said, “marks an important step in what buying local looks like in Mecklenburg County.”

After all phases are built, the project will have roughly 100 new hires. Some of those will be filled with the help of local nonprofits like Freedom Fighting Missionaries, which aims to help formerly incarcerated individuals. But the priority, Wyatt said, “will be to hire from the community within walking distance.”

The facility will aim to help meet the needs of every lifestyle — from those seeking to purchase raw ingredients to those in need of pre-made meals and everything in between.

For those without cooking experience, the teaching kitchen will provide a space for community members to learn new recipes and prep ingredients on-site. The goal is to meet residents where they’re at. “It has to be as easy and convenient as going down the street to a fast food restaurant,” Wyatt said.

Both Peake and Wyatt say building up regional food systems like this can help close the widening divide between consumers and the source of their food.

Evidence increasingly shows that modern agricultural practices have reduced the nutritional value of fruits and vegetables. The pair says keeping food local will help better connect residents with fresher food, which contains more nutrients. “We need to create these regional food systems for all of us,” Wyatt said — adding that food access is a growing issue even outside of poorer neighborhoods. “In the years to come, your zip code is not going to be able to protect you.”

For Peake, the project will also provide benefits that are near and dear to his heart. By providing new amenities, jobs, and food options, he says the facility could inspire hope for the West Charlotte and Hoskins neighborhoods where he grew up.

As he spoke with Courthouse News in the parking lot of Mr. Quick last week, Peake waved at passersby and called out to drivers on South Hoskins Road, who honked when they recognized him. Then he motioned to the skeleton of the egg- processing plant. Fenced off behind the store and long abandoned, this is where the Farm Trust’s new facility will be.

To Peake’s mind, it will be much more than a place to buy groceries. “We want to treat this as a gathering place,” Peake said. With the teaching kitchen and event space, he hopes it can become a hub for a community in need of more resources.

It could be a while before Hoskins once again returns to Happy Days — but for a neighborhood that’s long struggled with a lack of healthy food options, it’s a start. “This is bigger than all of us,” Peake said. “It’s not one organization, it’s not one person. This is something that’s truly bigger than all of us.”